|

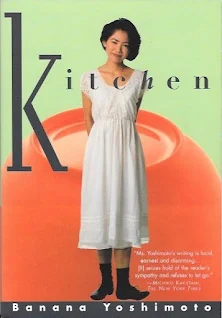

| (Cover Artist: Sigrid Estrada) |

One of the things that makes Banana Yoshimoto's 1988 novella Kitchen so unique is how approachable the story is. A dry summary of Kitchen's plot can easily cause the book to sound needlessly intense, with the words "loss" "tragedy" and "grief" appearing at least several times in a single paragraph. This is understandable, since Kitchen is primarily concerned with the process by which its protagonist, Mikage, comes to terms with the death of her grandmother--an event that in and of itself requires she acknowledge that she now has no surviving family members to turn to for comfort or support in her life.

That such a story might be difficult to read would be almost inevitable in the hands of most authors, and yet Yoshimoto addresses this material in such a simple and earnest way that it's easy to forget how weighty this book's ultimate subject really is. What Yoshimoto does with this book is take emotionally difficult material, and write it in a way that makes these topics approachable all while also never obscuring their reality.

Kitchen opens by introducing the reader to Mikage Sakurai--a woman in her early twenties living alone in a solitary apartment. In simple first-person narration, the story begins with Mikage seemingly randomly describing to the reader her love of kitchens, and specifically the various types of kitchens she has encountered in her life. While vividly written, there's something slightly off about these passages, with Mikage's admiration of kitchens and the experiences she's had of them quickly taking on a slightly eccentric element. This quality is demonstrated by the book's very first paragraph, which reads:

The place I like best in this world is the kitchen. No matter where it is, no matter what kind, if it's a kitchen, if it's a place where they make food, it's fine with me. Ideally it should be well broken in. Lots of tea towels, dry and immaculate. White tile catching the light (ting! ting!). (p.3)

This paragraph sets the tone for the ensuing chapter, with Mikage's narration coming across as at first quirky, and then (with the use of the onomatopoeia "ting ting") slightly off-putting. This unease gradually builds further in the reader as the scene continues, with it soon becoming clear that what Mikage is discussing in this chapter is not actually her love of kitchens, but rather a difficult emotional experience which she is actively attempting to articulate to herself through the meaning that kitchens have always represented for her.

It's only slowly, as she continues describing kitchens and her love for them, that Mikage almost off-handedly mentions to the reader that her grandmother has recently died, and then links this event back to her love of kitchens by stating that when she herself one day dies, she would like for it to be in a kitchen (this being the place where she and her grandmother spent so much time together).

"When I'm dead worn out, in a reverie, I often think that when it comes time to die, I want to breath my last in a kitchen. When it's cold and I'm all alone, or somebody's there and it's warm, I'll stare death fearlessly in the eye. If it's a kitchen, I'll think 'how good.'" (p.4)

It's through this process that Yoshimoto introduces the reality of Mikage's situation, slowly revealing how the off-key nature of Mikage's words were due to her own entirely natural struggles with grief. Critically here is the fact that Yoshimoto's depiction of Mikage's grief is not overdone. There are no extended sequences in which the author has her protagonist writhe on the floor in despair, or cry out in emotional agony at her grandmother's death. For that matter, it's difficult to even say that Mikage's grieving process is overtly unhealthy, as even when she states that she hopes to one day die in a kitchen, she does so in a context that makes it clear to the reader that this wish isn't self-destructive. Instead, Yoshimoto simply allows these scenes to sit quietly in the reader's mind, demonstrating how Mikage contemplates her own experience of grief on her own terms.

Yet this grief is soon interrupted when she is visited by Yuichi Tanabe, a boy about her age who attends the same college as she. Having known Mikage's grandmother from the flower shop where he works, Yuichi invites Mikage to have dinner with he and his mother, and in this way Mikage comes to suddenly be adopted by this tiny extended family of which she has no direct relation. When Yuichi's mother, Eriko, offers that Mikage move in with them while she searches for a cheaper apartment, Mikage agrees, and as a result begins her own slow healing process by forming a new set of social connections beyond the isolated two-person family in which she and her grandmother had previously lived.

However, this is not all there is to Kitchen's story. Central to this novella about grief is also an additional element regarding gender identity and transphobia. Just as Mikage has been isolated after the death of her grandmother, Yuichi and his mother Eriko are likewise shown to be cut off from wider society in a similar manner. Eriko is, as Yuichi casually explains to Mikage early on, originally his biological father--this woman having transitioned from male to female decades earlier after the death of her wife. This choice on Eriko's part to come out as a trans woman lead to her being disowned by her own family, requiring that she raise Yuichi entirely on her own. It was in part this loneliness the two feel that lead to Yuichi forming a friendship with Mikage's grandmother.

Yoshimoto's choice to include in this story a family (Yuichi and Eriko) which defies traditional notions of gender, and who help guide Mikage through her own grieving process, is a significant element of Kitchen. Repeatedly throughout the story, Mikage continually relates to the reader her love of food and of kitchens, regularly falling back on the task of preparing meals for Yuichi and Eriko as a method not only of coping with her grief, but also finding meaning in her life.

Were Yoshimoto to present Mikage as being adopted into a more traditional family that conformed to conventional gender roles, then the nature of the role that Mikage gravitates toward in this story (that of a woman who finds purpose in life by preparing food for others) would have caused this text to risk reenforcing a series of harmfully sexist stereotypes. Instead, Yoshimoto very deftly avoids this danger by establishing Mikage's personal convictions about her own purpose in life (caring for others) to exist in the context of a family that is not only anything but traditional, but far stronger as a result.

Ultimately it's Eriko herself who articulates to Mikage what seems to be Yoshimoto's overarching statement regarding this story, and why Mikage cares about kitchens so much.

"It's not easy being a woman," Eriko said one evening out of the blue.I lifted my nose from the magazine I was reading and said, "Huh?" The beautiful Eriko was watering plants from the front of the terrace before she left for work."Because I have a lot of faith in you, I suddenly feel I ought to tell you something. I learned it raising Yuichi. There were many difficult times, god knows. If a person wants to stand on her own two feet, I recommend undertaking the care and feeding of something. It could be children, or it could be house plants, you know? By doing that you come to understand your own limitations. That's where it starts." As if chanting a liturgy, she related to me her philosophy of life. (p.41)

Through moments like these, Yoshimoto's novella establishes itself as something much more complicated than the outwardly simple story of how Mikage overcomes grief by finding a new family in which to live. Instead, Kitchen is a novella which explores the way in which Mikage's own emotional pain is something that is healed not only as a result of the care which Yuichi and Eriko show her, but also the way which she is able to then in turn care for others.

This theme becomes especially important in the book's second half, when Mikage moves out of the Tanabe household and starts a life for herself anew. Beginning a career working backstage for a celebrity chef, Mikage nevertheless soon comes to be drawn back into the lives of Eriko and Yuichi, this time in a very different context that inverts the supportive roles which these characters had previously inhabited.

In a way it's easy to characterize Kitchen's story as a tragedy, since if I related only the core plot points of this novella without context, they would probably make the story sound emotionally draining to read. However, the thing that becomes Kitchen's most defining element is the gentle way it approaches even its most emotionally weighty material. Ultimately Kitchen isn't so much a novella about loss and grief, but instead a novella about how a small non-traditional family of characters cope with hardship, supporting one another as they find comfort in their mutual company.

There's something reassuring about that subject, and it's that reassuring quality that comes to define Kitchen's story, no matter what ordeals its characters face.