|

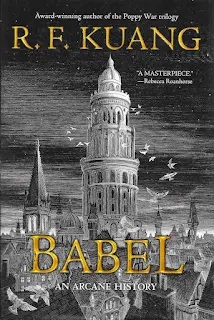

| (Cover Illustrator: Nico Delort) |

Yet despite Babel's early accomplishments, the novel's ending veers sharply away from these subjects. In the place of the book's initial themes exploring how language can be used to strengthen unjust social hierarchies, Babel's final chapters jump into a new narrative exploring whether or not violence is a necessary component of political change. Yet despite the importance of this new subject, these elements are introduced so late in the plot that there isn't time to fully examine the themes they bring to the story before that story concludes.

The result is that Babel becomes a book which initially takes as its primary subject the ways in which language can be used to hinder communication rather than facilitate it, with its characters routinely finding that they have been forced to ignore vital realities in their lives, going so far as to insist to others that the repeated experiences of racism and sexism they are forced to endure on a daily basis do not exist. Yet in spite of these themes, and the skill with which they are explored, Babel ultimately ends with a sequence wherein the novel's own narrator ultimately insists to the reader that this story is actually an entirely different narrative from the one we've so far been following. In the process, Babel effectively ends by enacting against itself the very same linguistic violence which it had earlier criticized, with even the narrator insisting to the reader that this story is communicating a message that is very different from the one it is clearly expressing.

Babel (Plot Summary)

Kuang's story begins in the early 1800s, with the novel opening in the home of a boy living in the city of Canton whose family has recently died of cholera. This boy (whose name is never spoken, but who we quickly come to know solely by the English language alias of Robin Swift) has already spent days stricken with a paralyzing fever. Yet as the story begins, Robin is abruptly rescued by a British linguist, Professor Lovell, who appears spontaneously at his bedside.

Having years earlier hired a live-in housekeeper to give Robin private English lessons, Lovell conveniently (perhaps too conveniently, in fact) just happened to be passing through Canton at the exact moment when the cholera epidemic hit. As a result, after visiting Robin's home and finding the child whose education he had funded to be dying beside the body of this boy's recently deceased mother, Lovell immediately uses a mysterious silver bar to magically cure Robin's illness, and then offers him an impossible choice between two stark futures. Either Robin can accompany Lovell back to England on the condition that he dedicate the rest of his life to the study of languages, or he can remain in a city where he has no surviving relatives, condemned to slowly starve while the plague which claimed his family rages on around him.

Naturally Robin (who is just six years old at the time) has no choice but to accept Lovell's offer, and in this context is adopted by a total stranger and taken from the only home he's ever known. Subsequently living in England for over a decade as Lovell's ward, Robin is eventually inducted into the Royal Institute of Translation--a college in Oxford where Lovell teaches, and which, due to the school's being housed in an imposing marble tower, is known more colloquially as simply "Babel."

It's at Babel that Robin begins studying the supernatural branch of linguistics that has in this novel's alternate history world formed the driving force behind British and American colonialism--silver-working. Via silver-working, English-speaking linguists have found ways to exploit a supernatural power inherent in all acts of translation. By inscribing upon specially designed silver bars so-called "match-pairs" of subtly contradictory English and non-English terms, silver-workers can physically manifest into reality the meanings and intentions which their translations have left unexpressed. Thanks to the powerful effects which silver-working produces, British ships now sail faster than any other vessels on Earth, while carriages move without the aid of horses, and factories run with an inhuman (and for their workers frequently deadly) speed and efficiency.

More concretely for Robin, as a student at Babel he encounters for the first time in his life an uneasy sense of community and belonging, with many of his fellow classmates sharing a similarly far flung and isolating background to his own. Foremost among the friends whom he meets in his classes is Ramy, a boy from Calcutta, India, who like Robin was forcibly separated from his family at a young age by a wealthy British businessman who was eager to fund the education of one of Babel's future translators. Then there is Victoire, a first-language speaker of Haitian Creole who was raised in indentured servitude in France, but who escaped by smuggling to Babel an application letter promising to study at the school if the administrators agreed to pay off the family who claimed (in violation of recently passed laws abolishing slavery) that she was their property. Finally there is Letty, the white daughter of a famous British admiral who has studied languages all her life, but whose gender meant that her wealthy father only allowed her to apply to Babel because of the politically awkward fact that her academically disinclined older brother died before he could complete his degree.

Yet despite the community which Robin finds at Babel, he also quickly discovers that his place at this school conceals a sinister reality. Not only is Babel a cornerstone of British and American colonialism, with many teachers openly profiting from the ongoing slave trade in the Americas even as many of their students are survivors of this same practice, but even the egalitarian approach towards education which Babel seems to champion by deliberately recruiting students from socially and linguistically underrepresented backgrounds is soon shown to be built atop a hollow utilitarianism.

As languages from all over the globe have come to be subsumed into the English vernacular, the critical cultural and linguistic differences on which the power of silver-working depends have started to fade. Without previously unstudied languages for Babel to exploit (languages which Robin, Ramy, and Victoire all conveniently happen to already be fluent in), silver-working will inevitably vanish from the world entirely, and with it the tactical and economic advantages upon which the corrupt institutions of all of colonialism depend.

It's in this way that Robin slowly reaches the bleak conclusion that it was Babel's need to exploit his language of Cantonese that compelled Lovell to rescue him from the cholera epidemic all those years ago. Likewise, as Robin comes to more fully grasp the true nature of his research into silver-working, and the exploitative context in which that research is being conducted, he also begins to struggle with the growing awareness that despite the community he has found at Babel, it is not so much he who is studying silver-working, but the entire field of silver-working which is, essentially, studying him.

Review

For much of Babel's story, it's this focus on the power imbalance underlying the study of silver-working that forms a strong core subject for the novel. From the book's opening pages onward, Kuang creates a multifaceted examination of the social and political themes animating her plot, with Robin, Ramy, Victoire, and to a lesser extent Letty all discovering that their places at Babel are inherently fraught due to the exploitative contexts in which they were admitted. Despite receiving research scholarships that easily pay for their living expenses, all four characters still live under the constant threat of what will happen to them if they ever choose to cut ties with Babel, and face the full force of the institutionalized racism and sexism which continues to exist beyond the school's walls.

This framing, when coupled with Kuang's building exploration of the veiled bigotry present in Babel's faculty itself, allows the novel to take as its core subject an examination of the nature of social privilege. Much of the tension of the book's early half hinges on Robin's gradual realization that even despite the sense of belonging which he has found at this school, his own place at this institution is an inherently coercive one.

One scene appearing very early on foreshadows this dynamic. Shortly after Robin is rescued by Lovell at the start of the book, the two attempt to board a ship scheduled to depart from Canton for London called the Countess of Harcourt. However, when they arrive at the port where the Countess is docked, Robin and Lovell find that their way is blocked by a disagreement that's broken out between an impoverished Chinese labourer, and a white member of the Countess's crew. This labourer (who is unnamed for the duration of the scene) has purchased a contract allowing him passage on the Countess, and yet one of the ship's crew-members has refused to abide by this contract's terms, instead declaring (in racially explicit language) that he will not allow the labourer on board his ship.

Due to this dispute, Lovell (who speaks only Mandarin, not Cantonese) ushers Robin forward, demanding that he "translate" so as to resolve this disagreement. Yet while Robin initially assumes that Lovell intends for him to literally relate the terms of the labourer's contract into English for the Countess's crewman, he quickly realizes that this is not the case. Soon, the entire scene comes to revolve around the ambiguity of Lovell's command that Robin "translate," and how the meaning of this term changes depending upon whose words are translated in this situation, and for what purpose.

‘Robin.’ Professor Lovell was at his side, gripping his shoulder so tightly it hurt. ‘Translate, please.’

This all hinged on him, Robin realized. The choice was his. Only he could determine the truth, because only he could communicate it to all parties.

But what could he possibly say? He saw the crewman’s blistering irritation. He saw the rustling impatience of the other passengers in the queue. They were tired, they were cold, they couldn’t understand why they hadn’t boarded yet. He felt Professor Lovell’s thumb digging a groove into his collarbone, and a thought struck him—a thought so frightening that it made his knees tremble—which was that should he pose too much of a problem, should he stir up trouble, then the Countess of Harcourt might simply leave him behind onshore as well.

'Your contract's no good here,' he murmured to the labourer. 'Try the next ship.'

The labourer gaped in disbelief. 'Did you read it? It says London, it says the East India Company, it says this ship, the Countess--'

Robin shook his head. 'It's no good,' he said, then repeated this line, as if doing so might make it true. 'It's no good, you'll have to try the next ship.' (p.14)

The result of this moment is that Robin, having been confronted with the precarity of his own place on the Countess, chooses to lie to the labourer, telling this man that his contract refers to another ship even when he knows this fact to be untrue. In doing so, Robin upholds the bigotry of the white crewman, with it being this act that facilitates his own passage to England.

This sequence also foreshadows the themes embodied by silver-working itself. Despite being introduced very gradually over the course of the book's first half, the mechanisms through which silver-working operates are themselves eventually shown to closely mirror the dilemma Robin faced in this moment. Similar to how Lovell's command that Robin "translate" for the crewman held within it an implicit order that was continually left unspoken (that Robin translate the words of the white crewman into Cantonese for the labourer, not the terms of the labourer's contract into English for the white crewman), silver-working is also shown to be the process of using translation to strategically hinder communication rather than facilitate it. Moreover, it's ultimately this obfuscation of meaning which is ultimately shown to give silver-working its power. As an instructor at Babel cheerfully explains the process when introducing silver-working to his students:

'The basic principles of silver-working are very simple. You inscribe a word or phrase in one language on one side [of a silver bar], and a corresponding word or phrase in a different language on the other. Because translation can never be perfect, the necessary distortions--the meanings lost or warped in the journey--are caught, and then manifested by the silver.' (p.156)

This same scene then continues with the instructor producing a silver bar with the French word "triacle" inscribed opposite the English word "treacle." Yet while both terms refer to a dessert, the combination of these two words are revealed here to produce a supernatural effect curing minor illness. The stated reason is that despite the similarities of "triacle" and "treacle," the French word holds within its meaning an older connotation referring to an antidote for poison (sugar having originally been associated with medicine).

Finally, similar to how silver-workers use translation to manifest into reality the things they deliberately choose to leave unsaid, the nature of the community which Robin finds at Babel in his friendships with Ramy, Victoire, and Letty is likewise quickly shown to be subtly toxic due to the realities left deliberately unacknowledged by all four characters.

In one critical passage appearing shortly after the two first meet, Robin and Ramy spend several days at Oxford prior to starting their classes, forming a close friendship which endures for the duration of the novel. However, this initial sense of belonging is disrupted when both characters are confronted by a group of white students who object to Ramy's wearing official Oxford gowns. These students claim (based on Ramy's skin-color) that his wearing of these gowns is in violation of an unspoken rule, and openly threaten both he and Robin when they insist that Ramy is actually an officially admitted student.

After this altercation has ended (with Ramy and Robin both fleeing the scene as they are chased through the streets), the two silently reflect on how severely this experience has impacted their understanding of Babel as an institution, and their status within it. Yet in a moment that mirrors the process by which silver-working physically manifests into reality those things which have deliberately been left unspoken, both characters implicitly agree to never speak to one another of this incident, or even acknowledge what it has signified to them about this school.

There was no question about what had happened. They were both shaken by the sudden realization that they did not belong in this place, that despite their affiliation with the Translation Institute and despite their gowns and pretensions, their bodies were not safe on the streets. They were men at Oxford; they were not Oxford men. But the enormity of this knowledge was so devastating, such a vicious antithesis to the three golden days they'd blindly enjoyed, that neither of them could say it out loud.

And they never would say it out loud. It hurt too much to consider the truth. It was so much easier to pretend; to keep spinning the fantasy for as long as they could. (p.68)

Moments like these set Babel up to become a deeply multifaceted story, with the book's gradually expanding themes regarding cultural exploitation and appropriation often being reflected back at the characters in unexpected contexts. Just as how it's the meanings which silver-workers leave untranslated which their work manifests into reality, Robin also eventually learns that it's those aspects of Babel's research into silver-working which its students and teachers actively ignore that reveal this school and its research as the centers for colonial exploitation that they truly are.

Criticisms (Plot Spoilers Follow)

Had these themes represented everything that Babel as a novel embodies, then I think that Kuang would undeniably have created one of the greatest works of fantasy published in the last decade. Unfortunately, despite Babel's early strengths, the book changes focus in its final chapters, and steps back from this exploration of the racism and hypocrisy that define silver-working. In the place of these themes, the story turns itself into a political allegory exploring (as the novel's full title implied) "the necessity of violence" when enacting social change. Yet while this theme does initially fit with the book's prior examination of the cultural violence of silver-working, it's undertaken in such a rushed and self-contradictory way that it jars with the story that has preceded it.

Eventually, Robin is finally forced to cut ties with Babel--an act which, without giving too much of the plot away, results in he, Ramy, Victoire, and Letty working to found a resistance movement against their former school. Striving to decouple the knowledge and power which silver-working represents from the forces of colonialism, Robin and his friends soon begin working to single-handedly halt the oncoming Opium Wars between China and Britain.

There are many aspects of this turn in the narrative which I think could have worked, since after an entire novel in which Robin reluctantly aligned himself with Babel, in the end he, Ramy, Victoire, and Letty finally come to openly acknowledge the brutality of this institution and the harm that its research is doing to the wider world. This is an act which, in turn, requires that they all finally begin acknowledging the unspoken realities permeating their relationships with one another, and the truths they have so far refused to accept.

Unfortunately it's not just the rushed way that Kuang handles this critical story moment that strains the narrative, but also the stilted process by which she indicates to her readers what the new plot line that follows it is meant to signify. Not only do Robin and his friends attempt to organize a global resistance movement against all of colonialism while also technically fleeing arrest on charges of murder (a plot point which feels like it should be much more significant to the story than it actually is), but even the characters themselves progress through this newly introduced narrative by making a series of formulaic decisions that seem constructed with the explicit intent of dramatizing an overarching political message to the reader. Worse, this is a message that is not supported by the events of the actual story that is being used to convey it.

After vowing to put a stop to the colonialist policies upon which silver-working depends, Robin and his friends are initially divided as to how best to oppose their school and its research. Unsure whether their efforts to halt the Opium Wars should be a nonviolent revolution sparking change from within existing institutions of power, or a violent revolution using fear to challenge the authority of the state (definitions of violence and nonviolence which no one seems to realize are false), Robin, Ramy, Victoire, and Letty initially choose to engage in exclusively nonviolent tactics when opposing Babel's work. As a result, after briefly (but seriously) considering a plot to use dynamite to blow up a major shipping port in Glasgow, they instead choose to organize a letter writing campaign asking the British parliament to vote against the coming war with China. The book then proceeds to describe in detail how these characters use their skills as silver-workers to magically enchant these letters to fly through the air like birds.

This decision to choose nonviolence rather than violence is then immediately demonstrated in the coming pages to be catastrophically misplaced. Shortly after this letter writing campaign has very predictably failed (with parliament's members ignoring the group's flying letters, and voting in favor of war), almost every named character in the book is extrajudicially murdered by the authorities in a brutal police raid. In the wake of this tragedy, a grief-stricken Robin and Victoire, as the sole survivors of this massacre, conclude that violence is necessary when righting societal injustice, and then because of this realization immediately succeed in organizing an infinitely more effective student-lead uprising against Babel itself.

Had the book taken even a little time in this sequence to more meaningfully explore the dilemmas that exist regarding violent versus nonviolent activism, then I would probably have been more sympathetic toward what I think Kuang was attempting to demonstrate with this segment of the story. The dichotomy which Babel establishes between the initial letter writing campaign which the group organizes, and the later translators' revolution which Robin and Victoire lead, is one that explores the limitations of seeking to address social injustice from within existing institutions of power. Had the book verified to the reader that it was this subject that the story was exploring (rather than the supposed pointlessness of nonviolent activism itself), then the story in which this initial resistance movement fails due to its deference to the authority of a bigoted institution would have worked. After all, when Robin, Victoire, Ramy, and Letty decide to oppose Babel through non-violent means, they do so not by actively opposing this school, but instead asking another equally corrupt institution for aid.

However, rather than honestly depicting the nature of nonviolent activism, or even the deeply political reality of how the actions of members of already marginalized groups are often seen by those in power as intrinsically violent simply for challenging the status quo, Babel instead portrays nonviolence itself as being universally synonymous with appeals to institutional authority. There are many more types of nonviolent activism than letter writing campaigns to parliament, and yet this is all that the book's characters seem capable of imagining when they initially (mistakenly) decide that violence can do nothing to further their cause.

This oversight was highlighted for me by how, in a way that I don't think was intentional on Kuang's part, Babel actually does eventually come to favorably depict the nonviolent activism which the story initially dismisses. It's just that the book does so while also seeming to claim that this activism is an example of violence (very directly equating it to the aforementioned plot to blow up a shipping port in Glasgow). After Robin and Victoire lead the student uprising against Babel, the essential services which silver-workers provide all of British society are denied, with the translators whom the school has recruited from nations all over the world barricading themselves in the main tower and refusing to allow their languages and cultural knowledge to be further exploited.

Yet while this translators' strike is continually presented to the reader as being an example of violence--Robin even at one point echoes the words of an earlier character by observing that the supposed violence of this strike "shocks the system," and that he and his followers are now using the emotions of fear and hatred to compel their former oppressors to view them as equals (p.498)--the actual activities which the translators engage in are continually depicted as being nonviolent. While there are some instances in which people are injured as a result of this strike, and later on even killed, these events always appear in a context that removes from the book's characters any responsibility for their actions. When one teacher at Babel is shot by Victoire early on, it's only because he was actively threatening the lives of others while fully aware that he himself was in no danger. Even then this teacher's wounds are quickly indicated to be non-lethal.

Similarly, while the translators' strike eventually brings about a catastrophic national emergency as various social institutions built atop silver-working begin crumbling (sometimes literally) to the ground, the translators themselves continually work to mitigate the harm they know their strike will cause to the general public. For instance, when everyone learns that various British landmarks are in danger of being destroyed due to the lack of trained silver-workers maintaining their infrastructure, the group goes out of their way to warn parliament of the impending danger to the public--warnings which parliament is then shown to strategically ignore so foster further hatred against this movement and its cause. Even the ultimate destruction of Babel's tower at the book's conclusion is an event which is conducted by Robin in a highly controlled setting, with there being no potential for unintended loss of life.

Which is to say that in the few times when anyone is injured as a result of this supposedly violent uprising, or (later on) dies as an indirect result of this group's actions, these events are very overtly presented to the reader as having happened not because of anything that Robin, Victoire, or any of their followers have done. Instead, the devastation that the translators' strike brings about, when it emerges in the story, is paradoxically both cited as proof of this movement's efficacy, and also attributed to the malicious actions of the novel's perpetually unseen antagonists as they work to undermine Robin's revolution from the sidelines.

To be clear, this depiction of a nonviolent movement could have worked, since one aspect of how such tactics historically operate is by working to reveal the brutality of an unjust system. However this reading of the novel is hampered by the fact that Robin himself continually insists that he is engaging in an actively violent revolution, even as Kuang as author seems to be working to sanitize Robin's actions so as to make them more palatable for her readers. The result is a story in which all of British society grinds to a halt due to a supposedly violent strike, with Robin and Victoire's own followers nervously debating the ethics of their supposed use of violence to achieve their goals, all while Robin for his part insists that the only way their movement can succeed is if it works to incite fear in its enemies. Yet all of this unfolds despite the increasingly significant but nevertheless unremarked fact that all anyone in this movement is really doing is sitting quietly in a room in a tower while refusing to do research which benefits colonialism. Is this really what constitutes an act of violence? Alternately, is the labeling of this revolution as violent a form of violence in and of itself?

If we had had a moment in which Robin paused to consider the meaning of the word violence, and ruminated on what he personally feels this word signifies, then this would at least have established a framework within which his actions could be interpreted. We could, for instance, have had a scene in which Robin and Victoire debated whether or not they thought social change occurring outside of existing institutions of power is violent, since such change must by definition challenge the authority (and therefore by some definitions existence) of a governing institution. Alternately, we could have had a scene in which the characters referenced the novel's earlier exploration of language and word etymology by discussing the root meaning of the word violence itself, and debated with one another whether or not that meaning had to refer specifically to the infliction of physical harm on another person, or instead a more abstract disruption of the status quo (for whatever it may be worth, according to my computer's dictionary the term comes to English via a French word that shares the same Latin root as the word "vehement").

Instead, Kuang seems to assume that her use of the term violence to describe Robin's movement requires no further clarification, even when her story is actively proving otherwise.

Some Final Thoughts

I do want to end by saying that there was a lot that I loved about Babel. Despite the issues I had with the book's rushed ending, the novel's final pages do eventually return to the themes surrounding language and translation that had initially animated the story. Kuang's final image in particular is the perfect encapsulation of the book's exploration of cultural appropriation, with the entirety of this story concluding via a moment wherein Victoire, in flashback, casually mentions a phrase in her first language of Haitian Creole, and then (seemingly) refuses to explain this phrase's meaning when asked.

With this scene, Kuang ends the book itself almost by turning directly to her readers, and asking us to sit with the feeling of ambiguity that can come from allowing people agency over their own language and knowledge. More than anything else, it's this feeling of ambiguity (and Kuang's skillful examination of where it comes from), which the best aspects of Babel's story embody.

Had the entirety of Babel fully dedicated itself to exploring these themes, then I think this would easily represent the best story I have read this year. My problem is just that while one half of Babel is fascinating due to its dramatization of the power dynamics that can exist within acts of translation, the book falters in its final chapters when it strives to warp itself into a rushed exploration of an ethical dilemma whose underlying conflict is not supported by the story itself.

There's an amazing work existing within Babel's pages, it's just that, like the meaning expressed by the two words of a silver-working match-pair, that's a story which Babel leaves only half-told.